Yesterday my coworker Meredith and I were discussing retention rates and were stumped on what to call a certain retention metric. Specifically, what do you call the % of users that performed an event during the week following the user’s sign up date?

It’s an important metric to measure because for most services the sharpest drop-off will be the day users sign up so it’s useful to know what % of them return and use the service at some point in the week that follows.

I wound up tweeting about it and received a lot of responses which I’ll summarize below.

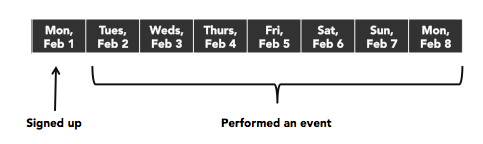

Before we dive into the options, it’s important to note that the day the user signed up is typically referred to as D0. Because users signed up that day, D0’s retention rate is always 100%. D1 then represents the % of users that were active on the day after sign up, D2 the % that were active two days after sign up, and so on.

Here are a few options with my 2c on their pros and cons:

Week 1 retention or Week 1 active – The main problem here is that it’s easy to misinterpret for folks seeing it for the first time: Does this mean a user was active 0 – 6 days after signing up (though this doesn’t make sense when you think about it because 100% of users are active on day 0) or 1 – 7 days (the first week after the sign up date)? Or if you confused it with the similarly-named 1 week retention does it mean 7 – 13 days (one week after the sign up date) or 8 – 14 days (one week after the day after sign up)? 😱

Post-first day active users, week one – +1 for specificity, -2 for the length :)

Week 0 retention or Week 0 active – This is less ambiguous, and is probably my second choice for what to call this metric. “Week 0 retention” would have to mean 1 – 7 days after sign up because a user isn’t considered retained on the sign up date and the zero makes it difficult to represent anything beyond days 1 – 7. The main problem for me is just that it takes too much thought and will constantly have to be explained to folks.

D1-7 – This is my favorite because there’s no ambiguity plus it’s nice and short. To me it’s hard to interpret this as anything but the metric we’re after. The downside is that it’s cumbersome to say out loud (“the day one to seven retention rate”) but in the end I think the pros outweigh that con. Hat tip Jan Piotrowski for suggesting it.

Thanks everyone for their feedback, especially Meredith who asked the question and whose insights on the naming I largely echoed in this post.